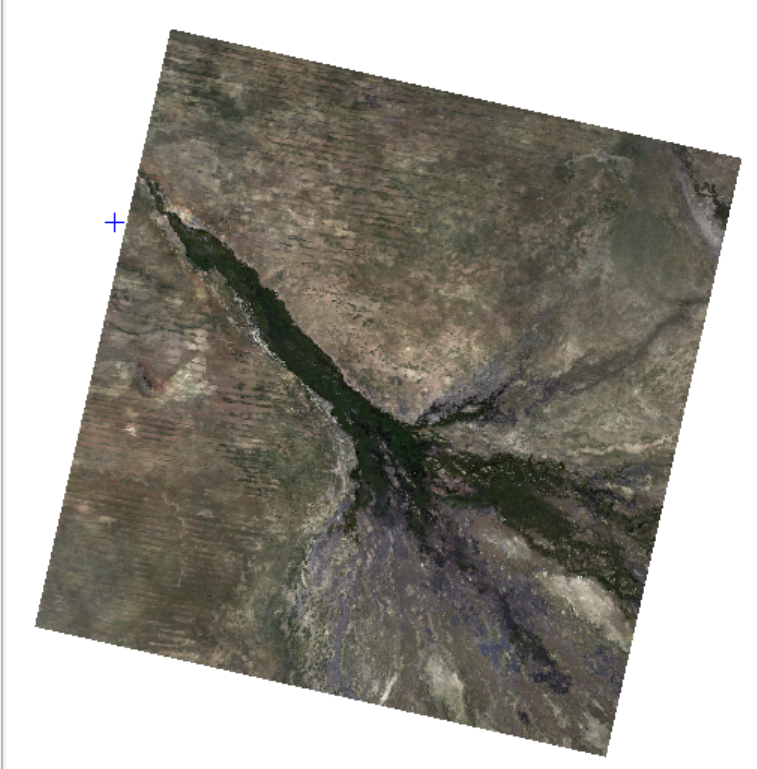

Okavango Delta, May 25th, 2019

The image provided captures the Okavango Delta in Botswana, one of the most remarkable inland delta systems in the world. Acquired by the Landsat 8 satellite on May 25, 2019, the data provides a striking visual of the region during what should be the peak of its annual flooding cycle. The most prominent feature is the "Panhandle" and the subsequent fan-like distribution of the delta, visible as a dark green vein cutting through the pale, arid landscape of the Kalahari Desert. This contrast is what makes the Okavango so unique: it is an endorheic basin where the Okavango River empties onto open land rather than into the sea, creating a massive oasis in an otherwise water-scarce environment.

Looking closely at the image, you can see the intricate network of channels and floodplains that define the delta’s core. However, what makes this specific 2019 data point particularly fascinating—and a bit concerning—is that it documents a period of severe regional drought. While May usually marks the arrival of floodwaters from the Angolan highlands, this image shows a delta that is much "thinner" and less vibrant than in average years. You can tell this by looking at the size of the green zones; instead of wide, saturated floodplains, the green is tightly confined to the main channels. The surrounding areas, which should be transitioning into seasonal wetlands, remain parched and dusty brown. The lack of "spillover" from the main arteries indicates that the river discharge was significantly lower than normal, a visual confirmation of the 2019 drought that gripped Southern Africa.

The metadata confirms that there was 0% cloud cover at the time of acquisition, providing a crystal-clear view of this ecological stress. This clarity is essential for researchers tracking the "flood pulse." Because the timing and volume of the flood are critical for the survival of migrating species, an image like this serves as a historical record of a year where the biological heartbeat of the delta was faint. We can see the land type mentioned in your selection—a complex mosaic of permanent swamps and seasonal floodplains—but the seasonal parts are clearly struggling to find water. This highlights why the Okavango is a UNESCO World Heritage site; its survival depends on a delicate balance of water inflow that can be easily disrupted by climatic shifts.

The use of Landsat 8 is particularly interesting for studying such a drought. Beyond just a pretty picture, the satellite's sensors capture data across various wavelengths, including thermal and infrared bands. For a researcher, the "interesting" part of this data isn't just the visible brownness, but the ability to use the infrared bands to calculate vegetation health indices. In a drought year like 2019, these digital values would show much lower "greenness" than previous years, helping scientists quantify exactly how much the biodiversity—from the tiniest aquatic plants to the largest elephant herds—was impacted by the water shortage.

Supporting Documents and Additional Resources

To learn more about how this data was captured and how to interpret the Okavango's unique landscape, you may find these resources helpful:

-

Landsat 8 Technical Details: Learn about the Operational Land Imager (OLI) and Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) used to capture this image.

-

USGS Landsat Collection 2: Documentation on the Level-2 Surface Reflectance (L2SP) processing used for this specific product.

-

The 2019 Drought Impact: NASA’s Earth Observatory often features articles on Southern Africa’s water cycles and how droughts are visible from space.

-

Okavango Delta Ecology: The UNESCO World Heritage Centre explains the biological importance of this specific land type.

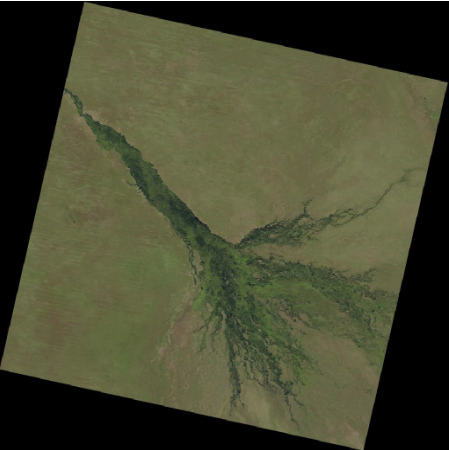

Okavango Delta, May 17th, 2025

This satellite image, captured on May 17, 2025, provides a fresh look at the Okavango Delta through the lens of the Landsat 9 satellite. This specific snapshot is particularly interesting because it represents a period of significant ecological recovery compared to the previous drought-stricken years. The Panhandle is exceptionally well-defined, appearing as a thick, saturated ribbon of deep emerald green that surges down from the north. Unlike the restricted, narrow channels seen in 2019, the 2025 data shows a delta that is spreading its fingers much wider across the Kalahari sands. The lushness is not just confined to the main river veins; there is a visible expansion of the surrounding wetlands, indicating that the floodwaters have arrived with robust volume and timing.

When analyzing the floodwaters in this 2025 image, they appear to be performing much better than expected, likely returning to or exceeding historical averages. This resurgence is largely due to a shift to La Niña conditions, which brought abnormally heavy rains to the Angolan highlands—the source of the delta's water—between November 2024 and April 2025. You can discern the impact by looking at the southern reaches of the fan, where the green hues are softer and more widespread, suggesting that the seasonal floodplains are successfully recharging after a decade of fluctuating drought. In a poor flood year, these distal areas remain parched and indistinguishable from the desert; here, they show clear signs of active hydration and budding vegetation, with reports indicating that water reached areas like Guma Lagoon earlier than in previous seasons.

The metadata reveals 0% cloud cover, which is a perfect scenario for remote sensing. It allows us to see the "land type" in high contrast: the dark, water-heavy core of the swamps transitions into a vibrant light green fringe of seasonal grasses before finally meeting the pale, olive-drab tones of the dry savanna. This image is a testament to why this region is a magnet for biological and ecological study. The sheer scale of the greening in 2025 suggests a healthy "flood pulse," which is the lifeblood for the delta's diverse species. From space, we can see the literal foundation of a food web—water reaching the floodplains triggers the growth of aquatic plants, which in turn support fish, birds, and the large herds of buffalo and elephants that migrate to follow the water.

The fact that Landsat 9 captured this ensures superior data quality. As a more advanced successor to Landsat 8, it features an upgraded OLI-2 sensor with 14-bit radiometric resolution. This means the satellite can differentiate between over 16,000 shades of colour, compared to just 4,000 on Landsat 8. This technical boost allows scientists to detect incredibly subtle differences in water-leaving radiance and plant health, even in the dark, "tea-colored" waters of the dense swamps. This makes the image not just a pretty view, but a vital piece of evidence showing how resilient this ecosystem can be when the rains in the Angolan highlands provide an ample supply of water.

Supporting Documents and Additional Resources

For those looking to dive deeper into how this specific 2025 data was generated and what it tells us about the region's hydrology, the following resources are excellent starting points:

-

Landsat 9 Mission Overview: Detailed information on the Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) and how it improves upon previous satellite generations.

-

Understanding Level-2 Science Products: A guide to Landsat Surface Reflectance and Temperature, which explains the "L2SP" processing level found in your metadata.

-

Okavango Research Institute (ORI): The University of Botswana’s ORI provides local expert analysis on the yearly flood variations and water quality.

-

NASA Earth Data - Worldview: Use the NASA Worldview tool to see how the delta's appearance changes day-by-day as the flood moves through the system.

Create Your Own Website With Webador